Soup wasn’t a once‑in‑a‑while thing back then — it was the backbone of the week.

Many families ate some kind of soup three, four, even five times, always with bread,

because it stretched whatever you had. And in the dead of January,

when the wind cut through the cracks in the timber walls and the livestock barns smelled of hay

and cold air, a thick pot of Erbseneintopf was more than food. It was warmth.

It was calories. It was survival.

So yes — in the, that split pea soup would have been warm,

thick, smoky from the bacon, and deeply satisfying.

Not fancy, not “special occasion,”

but the kind of everyday comfort that kept families going through long winters.

And that’s the part of the story German‑Americans feel in their bones today:

a simple pot of peas carrying centuries of practicality, thrift, and quiet comfort.

|

Ingredients:

1 ham hock or approx. or 1 cup of dice ham or bacon

2 quarts Chicken, beef or ham stock (8 cups)

You can make a stock with the ham hock

2 cups chopped Leeks

2 cups chopped celery root or celery stalk

2 cups chopped carrots (3 large)

1 lb (1 bag) Split Peas

salt and pepper to taste

1 tablespoon Marjoram leaves or ground (May substitute thyme)

2 bay leaves

a dash of nutmeg

6 Frankfurters with natural casing

printer friendly Metric Conversion Chart

|

Our German Heritage Recipe Cookbook

~~~~~~~~~~

Kitchen Tool Discussion

The Kitchen Project receives a small commission on sales from Amazon links on this page.

Full Affiliate Disclosure Policy |

The German soup kitchen starts with the "Deutche Holy Trinity" called Supengruen.

This is a centuries old combination or basic flavoring fo soup.

Leeks, would stay nicely in the garden, even if the ground was covered by snow.

and carrots and celery root wintered over in a basic root cellar.

The ham hock while doesn't have much meat on it, but still has a lot of flavor locked up between

the bones and sinew. that can flavor a whole pot of water into a flavorful broth.

.jpg)

While we don't have the gardens of yester-year or century, so if you can't find or afford celery root, celery works very well. It wasn't available in the garden in the middle of winter, and there were no supermarkets.

Chop everything to a medium dice, and be sure and give the leeks a wash, as soil gets into the leaves.

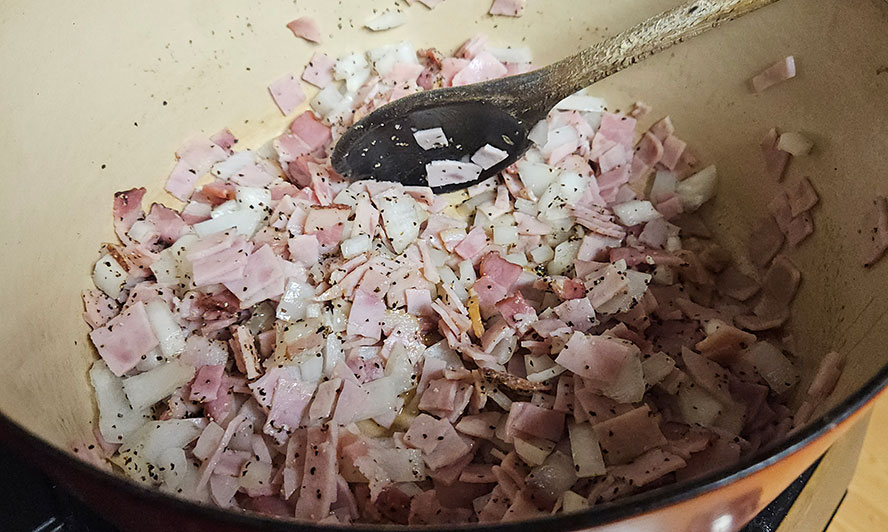

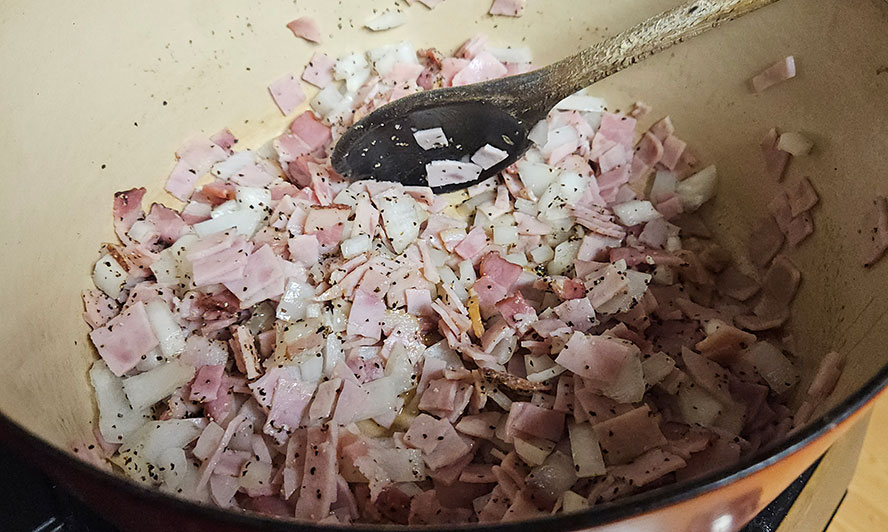

Meat was scarce when our relatives were getting through winter.

instead of 6 oz of meat per meal, a little bacon was used to flavor vegetables and dried peas.

Sweating the bacon and then saute the vegetables, herbs and spices, brings out more flavor. the bubbling fats and oils is a higher heat and unlock flavors and aromas that you don't get when you just boil the vegetables.

This is a culinary phenomenan called the Maillard reaction.

If you are interested in this scientific reaction you can read more about the "Maillard Reaction" here

Next add your stock and bring to a simmer. add the split peas.

Simmer for about 60- 90 minutes and the split peas will dissolve and the soup will be creamy.

You can leave it like this with the vegtables and meat in tact.

You can puree the soup so it is creamier. It is fun to float a Frankfurter or smoked sausage on top, for a nice contrast. If you do it is nice to use a large shallow bowl, that it will be easier to cut the sausage.

You can add large chunks of potato, and other vegetables and make a full meal out of it.

This is what Germans would call Erbseneintopf.

|

Maillard Reaction

When you Saute Vegetables

Sautéing vegetables and onions before adding liquid is a foundational culinary technique used to develop deep, complex flavors that boiling alone cannot achieve.

Flavor Development (Maillard Reaction): High-heat cooking (sautéing) triggers the Maillard reaction, a chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars that occurs at temperatures above the boiling point of water (starting around 285°F/140°C). Boiling is capped at 212°F (100°C), which prevents these savory, nutty, and toasty compounds from forming.

Mellowing Aromatics: Raw onions and garlic contain pungent sulfur compounds that can be overwhelming. Sautéing breaks these down, converting them into a mellow sweetness and earthy depth.

Caramelization: Sautéing draws out and concentrates natural sugars, especially in onions and carrots, leading to caramelization that adds a rich, sweet dimension to the soup base.

Extracting Fat-Soluble Flavors: Many aromatic compounds in vegetables and spices are fat-soluble rather than water-soluble. Sautéing in oil or butter extracts these flavors and carries them throughout the entire soup once the liquid is added.

Texture Management: Sautéing (often called "sweating" if done without browning) softens the rigid cell walls of dense vegetables like carrots and celery. This ensures they reach a pleasant, tender consistency during the simmering stage rather than remaining unevenly crunchy.

Concentrating Taste: Sautéing helps evaporate excess moisture from the vegetables, concentrating their "true" flavors before they are diluted by broth or water.

|

|

.jpg)